The interview with Lenin had been a matter of some difficulty to arrange; not because he is unapproachable - he goes about with as little external trappings or precautions as myself - but because his time is so precious. He, even more than the other Commissaries, is continuously at work. But at last I had secured a free moment and drove from my room, across the city, to one of the gates of the Kremlin.

I had taken the precaution at the beginning of my stay to secure a pass that set me free from any possible molestation from officials or police, and this gave me admission to the Kremlin enclosure.

Entrance to the Kremlin is naturally guarded; it is the seat of the Executive Government; but the formalities are no more than have to be observed at Buckingham Palace or the House of Commons. A small wooden office beyond the bridge, where a civilian grants passes, and a few soldiers, ordinary Russian soldiers, one of whom receives and verifies the pass, were all there was to be seen at this entrance.

It is always being said that Lenin is guarded by Chinese. There were no Chinese here. I entered, mounted the hill, and drove across to the building where Lenin lives, in the direction of the large platform where formerly stood the Alexander statue, now removed. At the foot of the staircase were two more soldiers, Russian youths, but still no Chinese. I went up by a lift to the top floor, where I found two other young Russian soldiers, but no Chinese, nor in any of the three visits which I paid to the Kremlin did I see any.

I hung up my hat and coat in the ante-chamber, passed through a room, in which clerks were at work and entered the room in which the Executive Committee of the Council of People's Commissaries holds its meetings - in other words, the Council Chamber of the Cabinet of the Soviet Republic.

I had kept my appointment strictly to time, and my companion passed on (rooms in Russia are always en suite) to let Lenin know that I had arrived. I then followed into the room in which Lenin works and waited a minute for his coming. Here let me say that there is no magnificence about this suite of rooms. They are well and solidly furnished; the Council Chamber is admirably arranged for its purpose, but everything is simple, and there is an atmosphere of hard work about everything.

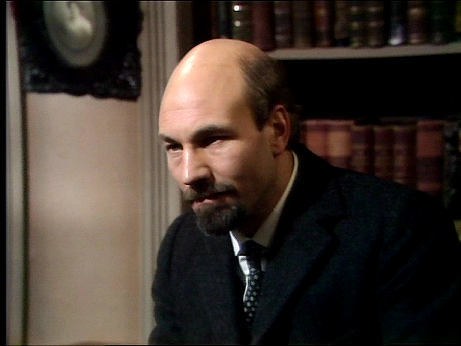

Of the meretricious splendour I had heard so much there is not a trace. I had but the time to make these observations, mentally, when Lenin entered the room. He is a man of middle height, about fifty years old, active, and well proportioned. His features at first sight seem to have a slight Chinese cast, and his hair and pointed beard have a ruddy brown tinge. The head is well domed, and his brow broad and well raised. He has a pleasant expression in talking, and indeed his manner can be described as distinctly prepossessing.

He speaks clearly in a well-modulated voice, and throughout the interview he never hesitated or betrayed the slightest confusion. Indeed, the one clearly cut impression he left on me was that here was a clear, cold brain, a man absolutely master of himself and of his subject, expressing himself with a lucidity that was as startling as it was refreshing. My companion had seated himself on the other side of the table to act as interpreter in case of need; he was not wanted.

After a word of introduction I asked what I should speak, French or German. He replied that if I did not object he would prefer to speak English, and that if I would only speak clearly and slowly he would be able to follow everything. I agreed, and he was as good as his word, for only once during the three-quarters of an hour that the meeting lasted did he stumble at a word, and then only for an instant; he had seized my meaning almost immediately.

I ought to state here that the thought of this interview had engaged me from the moment I had entered Russia. There were so many things I wanted to know, scores of questions occurred to me, and to secure the answers I longed to have would have required a discursive talk of hours had I begun my task with this interview. But by leaving it to the last my month's work had brought the answer to many of the questions, and others had been settled by a radiographic interview submitted from Lyons by a combination of American journalists.

It behoved me therefore to utilise to the best advantage the time rigidly apportioned- to me, wedged in between two important meetings. I had therefore reduced all my curiosity to three questions, to which the authoritative answers could be given only by Lenin himself, the head of the Government of the Soviet Republic.

He knew quite well who I was; he did know what I wanted. There could therefore be no question of preparation so far as he was concerned. I had spoken of my questions to only one man, the Commissary who accompanied me, and he became very depressed, and gave it as his opinion that Lenin would not answer them.

To his unfeigned astonishment the questions were answered promptly, simply, and decisively, and when the interview was ended my companion naively expressed his wonderment. The guidance of the interview was left to me. I began at once. I wanted to know how far the proposals which Mr. Bullitt took to the Conference at Paris still held good. Lenin replied that they still held good, with such modifications as the changing military situation might indicate. Later he added that in the agreement with Bullitt it had been stated that the changing military position might bring in alterations.

Continuing, he said that Bullitt was unable to understand the strength of British and American capitalism, but that if Bullitt were President of the United States peace would soon be made. Then I took up again the thread by asking what was the attitude of the Soviet Republic to the small nations who had split off the Russian Empire and had proclaimed their independence. He replied that Finland's independence had been recognised in November 1917; that he (Lenin) had personally handed to Swinhufvud, then head of the Finnish Republic, the paper on which this recognition was officially stated; that the Soviet Republic had announced sometime previously that no soldiers of the Soviet Republic would cross the frontier with arms in their hands; that the Soviet Republic had decided to create a neutral strip or zone between their territory and Esthonia, and would declare this publicly; that it was one of their principles to recognise the independence of all small nations, and that finally they had just recognised the independence of the Bashkir Republic - and, he added, the Bashkirs are a weak and backward people.

For the third time I took up the questioning asking what guarantees could be offered against official propaganda among the Western peoples, if by any chance relations with the Soviet Republic were opened. His reply was that they had declared to Bullitt that they were ready to sign an agreement not to make official propaganda. As a Government they were ready to undertake that no official propaganda should take place. If private persons undertook propaganda they would do it at their own risk and be amenable to the laws of the country in which they acted.

Russia has no laws, he said, against propaganda by British people. England has such laws; therefore Russia is the more liberal-minded. They would permit, he said, the British, or French, or American Government to carry on propaganda of their own. He cried out against the Defence of the Realm Act, and as for freedom of the Press in France, he declared that he had just been reading Henry Barbusse's novel Clarte, in which were two censored patches.

'They censor novels in free, democratic France!' I asked if he had any general statement to make, upon which he replied that the most important thing for him to say was that the Soviet system is the best, and that English workers and agricultural labourers would accept it if they knew it. He hoped that after peace the British Government would not prohibit the publication of the Soviet Constitution. That, morally, the Soviet system is even now victorious, and that the proof of the statement is seen in the persecution of Soviet literature in free, democratic countries.

My allotted time had expired and, knowing that he was needed elsewhere, I rose and thanked him, and, making my way back through Council Chamber and clerks' room to the stair and courtyard, where were the young Russian guards, I picked up my droshky and drove back across Moscow to my room to think over my meeting with Vladimir Ulianoff.